Rebecca Lauren, Guest Contributor

This post is part of a series on SRPR’s ongoing and evolving conceptualization of the Poetics of Emplacement. What do we mean by Poetics of Emplacement? SRPR’s editor, contributing editors, staff members and friends share their thoughts here.

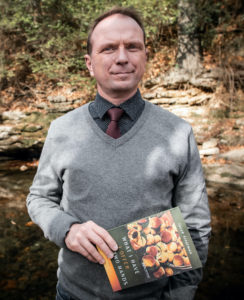

In the opening poem of my chapbook, The Schwenkfelders (2010, Seven Kitchens Press), I recount a beloved fable of my ancestors, a fable that explains their scattered settlement in Silesia before religious persecution brought them to a different set of valleys in Pennsylvania:

… one night, when hope got lost at the bottom

of some forgotten stewpot, the Devil

stuffed Schwenckfeld’s followers into a sack

and set off for the underworld—

spindly Santa Claus in red with no sleigh.

While soaring over Spitzberg,

snow caps gleaming beneath him,

the Devil snagged a corner

on the mountain’s peak.

Burlap seams split, spilling

Schwenkfelders into the valley.

Men’s bodies bounced like jacks;

women’s spun and splayed like unfurling yarn.

After the great fall, Schwenkfelder women

shook starlight from their heads,

stood and straightened bonnets.

While somewhere in the sky

the Devil hopped on one leg,

cursing a stubbed toe, the valley’s green womb,

the dazzled men and women with looms.

Like my ancestors, there is starlight in my head, a valley in my bones.

Through the historical reimaginings made possible by poetry, I explore the limited physical space available to Schwenkfelder women as homemakers in a valley. However, in The Schwenkfelders, I also express the myriad ways women resisted these constraints through acts of creation: marginalia in school cipher books, fraktur drawings and hand-written letters mailed beyond the valley and across the Atlantic.

Daphne Spain, in her theory of the construction of space, explains that “spatial segregation is one of the mechanisms by which a group with greater power can maintain its advantage over a group with less power…By controlling access to knowledge and resources through the control of space, the dominant group’s ability to retain and reinforce its position is enhanced.” As I piece together my own poetry and try to find space for it in the literary world, I recognize that I have much in common with my eighteenth- and nineteenth-century female ancestors who scribbled in the corners of whatever piece of paper they could get their hands on. Spain’s theory helps to frame for me how living in a valley – for women in particular, for women like myself – can be simultaneously restrictive and freeing, a womb that both gestates life and pushes it into the world.

Nestled in Central Pennsylvania, the Susquehanna Valley is where I grew up. It’s where my dad and his dad before him set down roots.

My mom, on the other hand, hails from Philadelphia but showed up in the valley one weekend to attend a Doobie Brothers concert with my dad. It was their first real date, and my mom wore a see-through shirt tied in a knot above her midriff along with tight bell-bottom jeans and platform shoes. She arrived at our town’s only bus station on Pine Street next to Rea & Derrick’s Drugstore. My dad met her there and said he just wanted to make a quick stop at his parents’ house before the concert – to introduce her to them, of course.

I think my mom wishes she’d worn a sweater.

When they stopped at the house, my dad’s mother gave my mom a thorough once-over and promptly asked her to drop her bags in the guest bedroom, located on the opposite end of the hallway from my dad’s room.

Later that night, when my dad and mom returned home from the concert, they were greeted my dad’s mother, awake at 3:00 AM on her knees scrubbing the refrigerator.

I have heard this story so many times that I can picture the Tupperware containers of food sitting on the countertop, my grandmother’s nonchalant greeting in which she tries not to sound too overprotective or eager, my mom’s blush of embarrassment, my dad’s chuckle. And I can hear my mom’s unending question, Who cleans their refrigerator in the middle of the night?

I believe this was the exact moment that my mom was introduced to the valley where even the hills themselves seem to watch over everyone like curious parents, waiting to ask where we’ve been and where we’re going.

Like my dad, I love the Susquehanna Valley. During my last year of high school, my best friend and I biked through our town to photograph our favorite places in case they were torn down in the next development scheme or worse – in case we moved away and forgot them.

I have a whole album of these photos – the playground equipment from our tiny elementary school before rural kids were bussed to the giant intermediate unit; the restaurant, Kinfolks, where my girlfriends and I would order large plates of mashed potatoes after high school; and the local paint store that shared the same name as a boy I’d had a crush on when I was twelve.

As the years passed, I watched friends marry young and buy quaint houses down the street from their parents, settling down in the valley as homemakers.

I was incredibly jealous.

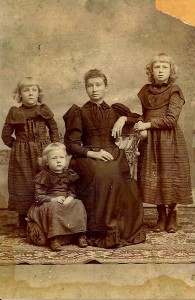

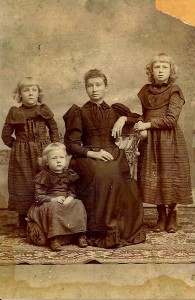

The mother in the photograph, Mary Lentz Yeakel, is the author’s great-great-great-grandmother. The youngest daughter, Mollie Blanche Yeakel, is the author’s great-great-grandmother and is featured with her sisters in the poem “The Night Mollie Blanche Yeakel was Named” in The Schwenkfelders. The photograph was taken circa 1893 in Williamsport, PA.

But like my mom, there were times when I felt uneasy in our small town, like I didn’t quite belong. And like the female Schwenkfelder ancestors I wrote about in my chapbook, I could not quite quench the desire to travel beyond the boundaries of hills that grazed the sky, especially if it meant freedom. Especially if it meant making sense of what I could not see.

So I joined the throes of high school graduates who moved away from the valley and who, even now, nestle a certain nostalgia of restlessness in their bones. Though we’ve backpacked through Europe, attended graduate schools, and moved to big cities to volunteer in soup kitchens, nothing’s felt quite like home. Our restaurants are chains named after days of the week, and our paint stores are run by corporate CEOs in New York City, not our ex-boyfriends’ parents. As women from a valley, we find ourselves constantly searching for our place in the world.

When the Schwenkfelders came to America, they were unable to secure a single plot of land, and many of their relatives remained in Silesia. As a result, women in the valleys of Pennsylvania relied on written correspondence to maintain their identity. Now that I have moved away from the valley, I feel that I too have fallen from some vast Silesian sky and awakened to the hard ground beneath my feet. Writing feels a bit like trying to shake the unsung poems from my head, so like my valley-bound ancestors before me, I turn to writing to bridge the gap, to remember the terrifying fall from the sky, and to find my sense of place again as a woman who is now “free” from the bounds of geographical segregation.

Daphne Spain divides the social construction of space into two categories: geography and architecture. To this list, for women in particular, we must add “artistic space,” or the use of space on a canvas, page, textile, or other creative medium. Virginia Woolf famously pines for “a room of one’s own.” Sojourner Truth asks, “ain’t I a woman?” when her story does not match up with society’s definition of femininity. Elaine Showalter introduces the gynocritical model of inquiry, examining the lack of scholarship on women in literature. Poet Adrienne Rich suggests that “diving into the wreck” allows us to recover lost female voices and encourage women writers to create despite a male-dominated literary world. Alice Walker goes “in search of our mothers’ gardens” to uncover creativity where it has be squelched. And today, VIDA, the organization famous for its pie charts depicting the percentage of women writers in literary journals each year, aptly illustrates how lack of creative space for women continues to directly correlate to lack of power in the literary world.

So sometimes, I revisit the valley in all its fertility and loam-rich possibilities. Sometimes, it is even in person. Most of the time, however, it is in my writing, as I imagine space beyond marriage and housework, beyond farmland sold to real estate developers, beyond bus stops and drugstores and male-dominated narratives.

As a woman writer, I avidly follow the VIDA count but write and submit my work anyway. Like the women who came before me, I create despite confinements, a river making its own way, carving its path.

Photo credit: Rebecca Lauren

≅

Born in Pennsylvania’s Susquehanna Valley, Rebecca Lauren lives in Philadelphia and teaches English at Eastern University. Her poetry has been published in Mid-American Review, Prairie Schooner, Southeast Review, and The Cincinnati Review, among others. Her chapbook, The Schwenkfelders, won the 2009 Keystone Chapbook Prize and was published in 2010 by Seven Kitchens Press. She received an MFA from Old Dominion University and serves as managing editor of Saturnalia Books.

Born in Pennsylvania’s Susquehanna Valley, Rebecca Lauren lives in Philadelphia and teaches English at Eastern University. Her poetry has been published in Mid-American Review, Prairie Schooner, Southeast Review, and The Cincinnati Review, among others. Her chapbook, The Schwenkfelders, won the 2009 Keystone Chapbook Prize and was published in 2010 by Seven Kitchens Press. She received an MFA from Old Dominion University and serves as managing editor of Saturnalia Books.