Michael Theune, SRPR Review Essay Editor

**Seth Abramson’s entire essay is now Available for free access**

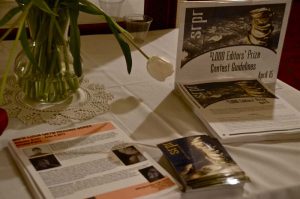

The new issue of Spoon River Poetry Review (38.1 (Summer, 2013)) is now out, and it is chock-full of treasures, including new poems by the likes of Rusty Morrison, Lyn Lifshin, Michael Burkard, Virginia Bell, Danielle Pafunda, Kevin Craft, Susan Briante, Sharon Dolin, Kit Robinson, and featured Illinois poet Allison Joseph. Along with this new work comes Seth Abramson’s review-essay, “The Golden Age of American Poetry Is Now.” [read the entire essay]

The thinking in Abramson’s piece comes at the right time. Abramson recently came to the defense of contemporary American poetry by publishing “Why Is Contemporary American Poetry So Good?,” an extensive response to an article in the Washington Post called “Why is modern poetry so bad?,” itself a meditation on Mark Edmundson’s essay “Poetry Slam (Or, The decline of American verse).” In his Spoon River review-essay, Abramson lays out in great detail why exactly American poetry currently is in a Golden Age. Anyone following this debate certainly will want to read “The Golden Age of American Poetry Is Now.”

Indeed, I believe Abramson’s review-essay is necessary reading for all those engaged with contemporary American poetry. I so greatly admire “The Golden Age” for a number of reasons. However, here I want to put Abramson’s piece in explicit conversation with Donald Hall’s “Poetry and Ambition”–a conversation Abramson invites by mention of Hall’s essay. For me, it is by listening in on this conversation that I come to more fully appreciate many of Abramson’s insights. I also find myself better able to formulate some questions I have about this being a Golden Age of American poetry.

In “Poetry and Ambition,” Donald Hall critiques a great deal of recent American poetry for its lack of ambition, for churning out McPoem after McPoem. One of the reasons for such debased production is the poetry MFA. Section 10 of Hall’s essay begins with a cry to “Abolish the M.F.A.!” And this undoubtedly should be the case if MFAs really are as Hall describes them, as “a garage to which we bring incomplete or malfunctioning homemade machines for diagnosis and repair.” While recognizing, in section 11, that “[m]ost poets need the conversation of other poets,” Hall still condemns the MFA, calling it an “institutionalized café” one that hires and pays mentors who then “make assignments” that then “reduce poetry to a parlor game.”

Abramson argues, however, that this understanding of the MFA is wrong. According to Abramson, the café has long been institutionalized. Additionally, understood phenomenologically, the MFA is a much more complex and multifaceted offering/participatory event. According to Abramson, the workshop itself provides an “intensely juxtapositive space,” a space which also opens further out: the MFA “is also the space in which MFA-seekers use social media, non- or quasi-academic program events, and impromptu social gatherings to share their other artistic obsessions–be they musical, dramatic, studio-art, couture, or literarily ‘off-genre.’” Abramson says that the avant-garde consistently has worked to move beyond objectification and commodification to more closely approach “the praxis of life.” Similarly, he tries to move discussion and assessment of the poetry MFA away from the (mere) objectification and commodification (and demagoguery) one might find in an analysis such as Hall’s to an understanding and appraisal of the MFA as praxis, as it is lived, experienced, and even co-created. In short, it is wrongheaded to think of the MFA (merely, or even centrally), as Hall does, as an assignment-giving institution.

And just as the writing program needs to be understood and investigated as praxis, so does the writer herself–and Abramson, I believe, does a masterful job of describing “the ‘Golden Age poetics’ produced by the children and step-children of the Program Era” (on page 110 in Spoon River Poetry Review (38.1)–this is vital reading). Again, Abramson notes that “Golden Age poetics cannot be treated primarily as a locus for canonization practices”–rather, now, we must “witness poetry as practice, as culture, as civic engagement, as way-of-life.”

Abramson’s review-essay is a masterful critical work, one that demands that its readers experience and interact with the full praxis of today’s writers and writing. However, even though Abramson’s piece generally eschews (and sometimes critiques) assessment–defined one time by Abramson as “making self-aggrandizing stabs at permanent assignations of value”–one part of the practice of contemporary poetry is evaluation. Judgments of value are being made all the time. So: if evaluation (a practice at the core of an essay like Donald Hall’s) is the blinkered remnant of old ways of conceiving poetry, how might the protocols of poetic evaluation be done away with, or productively revised? Should they be? Can they be? Can we even refer to the contemporary era of America as a “Golden Age” without some degree of evaluation being incorporated into that description? “Golden,” at least, often designates the best. (Why not simply refer to our current era as a “Very Productive Age”?) And, at least to my thinking, it simply is the case that there’s some amazing poetry being produced nowadays, including, for example, Frederick Seidel’s Ooga-Booga, Jorie Graham’s Place, D.A. Powell’s Cocktails, Arda Collins’s It Is Daylight, Laura Kasischke’s Space, in Chains. It is because of such works (and many others) that I feel we just may be in a “Golden Age of American poetry.” But without such excellent work I would not be as apt to make this claim. Is this an outmoded way to think?

I look forward to many, many people reading Seth Abramson’s truly significant review-essay, and continuing the conversation–perhaps here, or else in other venues–it has so powerfully engaged.

≅

Michael Theune is Review Essay Editor for Spoon River Poetry Review. Theune also is the editor of Structure and Surprise: Engaging Poetic Turns (Teachers & Writers, 2007), and the host of the Structure and Surprise blog. Along with Kim Addonizio, he co-edits Voltage Poetry, an online anthology of poems with great turns in them, and discussion about those poems. Theune’s poems, essays, and reviews have appeared in numerous publications. He is an associate professor of English at Illinois Wesleyan University.

Emily is from Boston, San Francisco, Fairbanks, Alaska, and Central Illinois. Holding a Ph.D. in English Studies and an M.F.A. in Creative Writing/Poetry, her work emerges at the intersections of writing studies, social justice pedagogy, trauma theory, film theory, and narrativity. In particular, she researches and publishes on students’ literacy learning in relation to issues of sexualized trauma. She has taught courses in academic writing, public writing, creative writing, gender studies, literature and film, and English as a Second Language. Emily is a Postdoctoral Researcher in Writing Pedagogy at The University of Delaware, and Managing Editor of Spoon River Poetry Review (SRPR).

Emily is from Boston, San Francisco, Fairbanks, Alaska, and Central Illinois. Holding a Ph.D. in English Studies and an M.F.A. in Creative Writing/Poetry, her work emerges at the intersections of writing studies, social justice pedagogy, trauma theory, film theory, and narrativity. In particular, she researches and publishes on students’ literacy learning in relation to issues of sexualized trauma. She has taught courses in academic writing, public writing, creative writing, gender studies, literature and film, and English as a Second Language. Emily is a Postdoctoral Researcher in Writing Pedagogy at The University of Delaware, and Managing Editor of Spoon River Poetry Review (SRPR).